WWII: Maginot Line | Normandy | V-Weapon Sites | Arnhem

Further afield: Crete

| Home Tracing Military Ancestors Travel Advice CWGC Cemeteries Iron Harvest News Book Reviews Glossary Links Contact Me Artois:

|

The Battle of Arras including the capture of Vimy Ridge (April-May 1917)

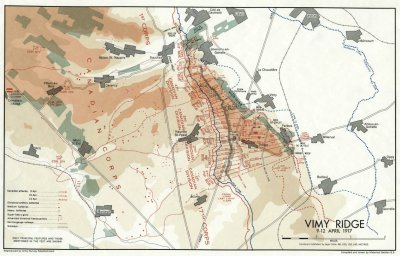

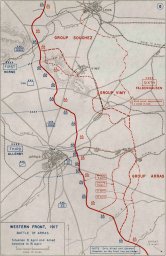

1. The British take over the line The German offensive at Verdun in February 1916, led to the British taking over the entire Arras/Artois front as French forces were moved to the Meuse sector to deal with the threat. It was also recognition of the British Empire’s growing strength on the Western Front as new volunteer armies were formed and major reinforcements arrived from Britain’s colonies. With much of the rest of 1916 dominated by the battles of Verdun and the Somme, British operations around Arras were initially concerned with local trench raids to promote a sense of aggression and domination over the Germans opposite and with mining operations to negate the topographical advantages that the Germans enjoyed. The British discovered, as the French had before them, that possession of the Vimy feature gave the Germans a perfect view of the whole area, giving them warning of any impending attack. To counter this the British began to build a network of tunnels or "subways" to move men and equipment up to the ridge without being spotted by the Germans. They were assisted by the fact that the underlying rock was chalk – a soft but stable medium through which to work. Altogether around 20 subways were dug – the longest, Goodman Tunnel, being 1,800 yards long. Once completed they contained command posts, regimental aid posts and the like. Some were connected to other tunnels or “boves” which had been excavated centuries before the war under Arras by its inhabitants. It was estimated that these could hold up to 11,000 men and their equipment. 2. The Battle of Arras – the Preparation In late 1916 the new French Commander-in-Chief, General Robert Nivelle, formulated a dynamic offensive plan. His successes at Verdun led him to believe that a massive artillery bombardment followed by an aggressive infantry assault could shatter the German line on the Chemin des Dames ridge in Champagne and bring about a decisive breakthrough. To assist this attack, he called on the British to launch a major offensive in the region of Arras to draw off German reinforcements prior to the much larger operation in the south. To achieve this, Field Marshal Haig had two armies. To the east of Arras, General Allenby’s Third Army, with eight assault divisions, would attack the German Hindenburg Line defences whilst, to the north of Arras, General Horne’s First Army, including the four divisions of the Canadian Corps, would take Vimy Ridge itself. But what made the British generals confident that they could finally break the German stranglehold on Arras? What would avoid another costly disaster as the French had suffered in May and September 1915? The answer lay, primarily, in the methodical and scientific use of artillery on a massive scale. The opening stages of the Battle of the Somme in 1916 demonstrated as clearly as the earlier Artois battles, that the British had neither the number nor higher calibre of guns necessary to destroy deep Germans dugouts and emplacements. Also, ammunition was insufficient and many shells failed to explode due to faulty fuses. For this operation, the British would use a higher density of artillery than ever before. For the assault on Vimy Ridge alone, General Byng, commander of the Canadian Corps, would have at his disposal 377 heavy guns, 150 4.5” howitzers and over 550 field guns (an increase in the number of yards per gun between the Somme and Arras of 1:2 for field guns and 1:3 for heavy). The guns would be kept firing using an unprecedented quantity of ammunition - 42,500 tons in total and improved quality control of the fuses in the UK following the “shell scandal” of 1916 would ensure a lower proportion were duds. In addition a new fuse, the “106”, was designed to clear barbed wire by exploding on impact.

The British also introduced new procedures to make the artillery more effective. Flash and sound ranging allowed German batteries to be identified and earmarked for destruction before the bombardment began and training focussed on rolling barrages to provide better protection for the infantry. The infantry themselves, particularly the Canadian units, developed tactics to exploit this new firepower. They exhaustively rehearsed assaulting behind a rolling barrage supported by trench mortars and used machine guns to fire over the heads of the leading infantry to suppress German front line fire. The Royal Flying Corps also contributed by concentrating 750 aircraft to patrol the front-line zone and, despite heavy losses, prevented German aircraft from interfering with the artillery preparations. Added to all this, the British and Canadians would use the “boves” and subways to move troops and equipment up to the front line and to accommodate command and control facilities and medical services protected from the danger of German artillery fire. 3. The Offensive Begins The artillery bombardment began on First Army’s front on 20th March 1917, being joined by Third Army’s artillery programme on 2nd April. It was an extraordinary show of strength. By the day of the assault on 9th April the British and Canadian batteries had saturated the German front with twice the number of shells fired prior opening of the Battle of the Somme and thirty times as much as the French had used in September 1915! At 5:30am on Easter Monday, in driving sleet and under a crescendo of supporting artillery and machine gun fire, the British and Canadian assault troops of two armies clambered out of their trenches and moved forward across no-man’s land.

On First Army Front, the southernmost two divisions of the Canadian Corps, 1st and 2nd came under heavy fire upon leaving their trenches but the force of their advance took them through six German trench-lines and the villages of Les Tilleuls and Thelus before they ended the day in capturing Hill 135. Further north, however, the strength of enemy positions on the highest point, Hill 145, prevented the 3rd and 4th Divisions from taking the remainder of Vimy Ridge until the following day when the soldiers could at last see out over the plain of Douai at countryside and villages untouched by war. Meanwhile, on Third Army’s front, there were equally resounding successes as 56th Division took the fortified village of Neuville Vitasse and some of the forward trenches at the northernmost end of the German Hindenburg Line. To their north the 12th and 15th Divisions of VI Corps advanced 2 miles and to their left the XVII Corps advanced as far as Fampoux – a penetration of three a half miles. It was the deepest since the Western Front formed in 1914! The Germans had been expecting a major offensive in the region, but the violence of the artillery programme and élan of the attackers took them completely by surprise. Up to 11th April the First Army took 4,000 prisoners and 54 guns for the loss of 11,000 men and the Third Army, 7,000 prisoners and 112 guns for the loss of 8,238 casualties. The capture of Vimy Ridge was a huge achievement and one that was to give the Allies a vital breakwater during the German offensive of March and April 1918. The battle also fostered a new spirit of identity in the emerging Canadian nation as well as demonstrating that a well co-ordinated artillery/infantry attack could capture and hold a major defensive feature.

4. The Aftermath Unfortunately, the successes of the first two days could not be maintained as the British advanced their artillery and supplies had to be brought forward over ground shattered by shellfire. Moreover, the Germans reorganised their defence and poured counterattacking divisions into the Arras sector to prevent a breakthrough. At Gavrelle and Monchy le Preux the British advance was halted and almost reversed by these reinforcements. Further south, in the Fifth Army sector, an attack on the Hindenburg Line proper by the Australians ended in disaster when a promised artillery barrage failed to materialise and supporting tanks broke down or were disabled before reaching the German wire. To add to the British commands’ problems, General Nivelle’s huge offensive in Champagne had been another costly failure and the Battle of Arras would have to be continued to prevent German reinforcements being sent south. Fighting continued throughout April for ever more limited objectives. Artillery barrages became more disorganised, troops became tired and weary and casualties mounted. The Battle of Arras culminated in May in a bitter and bloody two-week slugfest for Bullecourt village, which decimated six British and Australian divisions. In 39 days of action since 9th April, the British, Canadians and Australians suffered 159,000 casualties – the highest daily rate for any major offensive that they undertook in the First World War. Conclusion The Germans never retook Vimy Ridge for the remainder of the war – the feature acting like a breakwater as German armies attacked to the north and south of it during their Spring 1918 offensive. When the war ended it was an obvious place for the Canadian Government to construct its National Memorial to those who had been killed in France and had no known grave - its two pylons reaching into the sky are visible for miles around. But as the visitor travels through this region thought should also be spared for those others who lie in Artois – French, German, British and Australian. Perhaps most poignantly they include John Kipling, the only son of the poet and author, Rudyard. His shock and despair at the loss of his boy at Loos led him to dedicate much of his remaining years to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. It is his heartfelt words, which are inscribed on so many of the graves in the surrounding countryside, "A Soldier of the Great War. Known unto God." |