WWII: Maginot Line | Normandy | V-Weapon Sites | Arnhem

Further afield: Crete

| Home Tracing Military Ancestors Travel Advice CWGC Cemeteries Iron Harvest News Book Reviews Glossary Links Contact Me Crete:

|

Crete - Brief HistoryThe German airborne invasion of Crete on 20 May 1941 was one of the most audacious military operations of the Second World War. With the Greek mainland already lost to the Allies and Hitler turning his attention to an assault on the Soviet Union, it was envisaged as a speedy way to end the Balkan campaign and secure the Axis Powers' southern flank. Further, German occupation of Cretan airfields and the Royal Navy anchorage at Souda Bay would threaten the entire British position in the Eastern Mediterranean and open Egypt itself – the vital hinge of the British Empire - to direct air and naval attack.

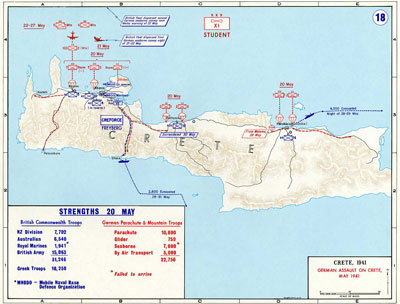

The German paratroopers (Fallschirmjäger) had originally been formed in 1936, although it was not until the Czech crisis of 1938 that they and other formations were grouped into the first airborne combat division – 7th Fliegerdivision led by General der Flieger Kurt Student. Student first unleashed his Fallschirmjäger during the invasion of Norway in April 1940. A month later, during the invasion of France in May 1940, they secured their renown by capturing the fortress of Eben Emael from the air – their tough training and experience in battle now marked them out as an elite unit. For Crete, Student planned a combined parachute and glider assault by the Luftlande Sturm Regiment and the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Regiment on the airfield nearest the Greek mainland – Maleme, and the approaches to the coastal town of Hania, the centre of British resistance. Once the airfield was under German control he would fly in the 5th Mountain Division to secure Hania and the rugged interior of the island. Other parachute drops by the 1st and 2nd Fallschirmjäger Regiments would be made against the other main towns on the island further to the east, Rethymno and Iraklio. A seaborne element would cross the Aegean as further reinforcement.

German intelligence reckoned there to be only around 5,000 British infantry troops based around Hania where they protected the naval base at Souda Bay and the Maleme airfield. But German estimates were hopelessly out of date. Evacuations from Greece and reinforcements had swelled the defenders to 42,000 in the Hania area and nearly 50,000 throughout the island. The Fallschirmjäger were flying into a trap! However, despite having a superiority in manpower and even being aware of the German strategy through ULTRA intercepts, the New Zealand commander of the garrison, Major General Freyberg VC, made a fatal misinterpretation of the intelligence. He attached equal importance to the German seaborne assault as to the airborne one. This fatal error was to seriously hamper his ability to react to the landings and to mount an effective counter-attack.

Preceded by a massive aerial bombardment delivered by the Luftwaffe to neutralise anti-aircraft defences (the few RAF fighters being driven off by attacks in the weeks before), the Ju-52 transport aircraft and DFS-230 gliders carrying the assault forces began to sweep across the island from 0815. As the paratroopers dropped, however, they were struck by heavy ground fire from the British, Commonwealth and Greek infantry defending the island. Unprecedented though the Luftwaffe bombing had been, the fact that the paratroopers and glider infantry were making their assault in daylight, made them very vulnerable to the island's garrison.

At Maleme, it was close to a massacre as paratroopers and gliders landed on the flat airfield and were cut down in their droves by machine-gun and rifle fire. Only those who had fallen and alighted in the dry bed of the River Tavronitis just to the west of the airfield apron could find any cover. Further east, German airborne assaults against Rethymno and Iraklio made equally limited progress again with heavy casualties. By the end of the day none of the German objectives had been taken and casualties amongst the assault formations meant that many units were little more than cadres – at Maleme the III Battalion of the Sturm Regiment had lost two-thirds of its men. At this point, Freyburg should have taken decisive action and organised a counter-attack with all available forces along the coast road from Hania west to clear Maleme of the remnants of the German force. The continued fear of a seaborne invasion, however, hamstrung his decision- making and the forces sent west to tackle the airborne incursion were inadequate for the task[1]. Worse still, during the early morning of 21st May, the local New Zealand commander on Hill 107 which dominated Maleme airfield from the south, decided to abandon his position. He had faced increasing German attacks from the River Tavronitis during the previous day and felt he could not hold his positions on the 21st without reinforcement. This decision was key as it enabled the Germans to cover the airfield as they flew in Ju-52 transports carrying the 5th Mountain Division. It was the turning point of the battle.

With Maleme airfield lost and German reinforcements now being flown in, the remainder of the campaign saw a series of increasingly desperate engagements as the British made a fighting withdrawal from Hania and Rethymno on the north side of the island to the tiny fishing port of Safakion. Here on 31st May the exhausted survivors were eventually evacuated. A further 4,000 men were evacuated from Iraklio on the night of 28-29th May. The British, Commonwealth and Greek forces suffered 3,500 casualties and a further 17,500 soldiers became prisoners of war during the campaign. The Royal Navy lost over 1,800 sailors during their operations around Crete in support of the defence. The campaign had been a victory for Student and his Fallschirmjäger troops. But it was a costly one. The Germans had lost over 6,500 men killed and wounded in the operation most from 7th Fliegerdivision, which led the assault. Of these over two-thirds were killed – an usually high ratio of killed to wounded. This is partly explained by the fact that many isolated paratroopers were slaughtered by the defenders during the drop or shortly after reaching the ground where their billowing parachute would have been a major encumbrance and beacon and before personal weapons could be retrieved. Others wounded and alone, were killed by partisans and local villagers as they lay helpless in the olive groves that cover the island. The Fallschirmjäger would never make an assault drop again for the remainder of the war.

[1] The Royal Navy managed to destroy both German convoys out at sea and they never threatened the Cretan coast.↩

|