WWII: Maginot Line | Normandy | V-Weapon Sites | Arnhem

Further afield: Crete

| Home Tracing Military Ancestors Travel Advice CWGC Cemeteries Iron Harvest News Book Reviews Glossary Links Contact Me Normandy Landings:

|

Breaching the Atlantic WallThe disastrous Dieppe expedition clearly illustrated the importance of providing massive firepower support to the infantry if they were to have any chance of taking and exploiting their objectives in an assault landing against a heavily defended coastline. Immense naval and air bombardments would be required to destroy individual strongpoints and artillery batteries and disrupt the assembly of enemy reserves. Meanwhile, armour would be needed on the beach with the infantry to remove obstacles, engage seafront defences and clear routes off the beach for the following assault waves. Between 1942 and 1944 the Allies undertook a series of amphibious operations in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and the Pacific where they put these “lessons learned” into practice. Landings in North Africa and Sicily were largely successful although they faced only light opposition. In comparison, later landings in Italy at Salerno and Anzio skirted with disaster - both being the subject of determined and well co-ordinated counter-attacks by German armour and, at Salerno, the Luftwaffe. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the US Marine Corps fought a series of bloody encounters against an entrenched enemy, resulting in huge casualties to the assaulting infantry. Yet none of these operations could compare to the dangers and difficulties that would be faced in breaching the Atlantic Wall. In order to achieve this a massive combined land, sea and air operation, unparalleled in history, would be required, utilising a whole range of new and existing military and naval assets.

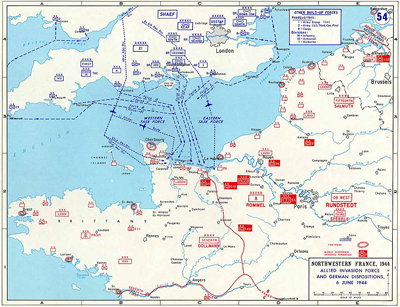

Paratroopers and Glider-borne Infantry During their invasion of France and the Low Countries in 1940, the Germans impressively demonstrated how parachute troops could use the element of surprise to seize objectives beyond the frontline. Yet barely a year later during the airborne invasion of Crete, their limitations became all too apparent. Lightly armed, and unable to receive equipment and reinforcements until the capture of vital airfields which were heavily defended, they were cut down in their thousands. Undeterred, both the British and Americans began to build their own such divisions consisting of paratroopers, glider-borne infantry and support units including light artillery and engineers. Training was tough, but it needed to be. The airborne divisions were expected to fight, sometimes for substantial periods, alone and without armoured support. Three divisions of airborne troops were tasked to land by parachute and glider on D-Day, outflanking the coastal zone defences. The British 6th Airborne Division would seize bridges across the River Orne and Caen Canal and blow others across the River Dives to the east, allowing seaborne and airborne reinforcements to secure and exploit the bridgehead whilst preventing German forces from interfering in the landings. They were also tasked with capturing the Merville Battery, north-east of Caen and preventing their guns from targeting the invasion fleet. Meanwhile, the American 82nd “All American” and 101st “Screaming Eagles” Airborne Divisions would land at the base of the Contentin Peninsula on the western edge of the invasion area. They had the dual role of securing the causeways across the flooded plain leading off “Utah” Beach and cutting communications between Carentan and Cherbourg – the only practicable route for German reinforcements. It was hoped that this would lead to an early capture of Cherbourg’s vital port facilities. The Seaborne Assault Forces Montgomery’s revised plan called for six seaborne assault divisions to land between the base of the Contentin Peninsula and the mouth of the River Orne on D-Day itself. From east to west they comprised the US 4th Infantry Division and the US 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions of the US First Army under Lt-Gen Omar Bradley and the British 50th Infantry Division, Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and British 3rd Infantry Division of Lt-Gen Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army. The beaches they were to land on were given code-names – the US 4th landing on “Utah”, the US 1st and 29th on “Omaha”, the British 50th on “Gold”, the Canadian 3rd on “Juno” and the British 3rd on “Sword”. Some of these units, such as the 231st (Malta) Brigade of the British 50th Division and the US 1st Division, the “Big Red One”, had previous experience of amphibious operations in the Mediterranean, but other soldiers had never been into battle before, let alone been involved in an assault landing. Extensive training of the assault divisions was, therefore, instigated. Full invasion exercises were carried out on the south coast of England, two of which starkly demonstrated the dangers inherent in such operations. During Exercise SMASH, a D-Day rehearsal using live ammunition by the British 50th Division, seven amphibious tanks sunk and six men drowned. Even worse, during Operation Tiger at Slapton Sands in Devon, nine German motor torpedo boats intercepted landing craft crowded with men of the US 4th Division. Two were sunk and over 700 men were killed. To assist the assault infantry in the opening stages of the landings, the Allies also intended to use unprecedented numbers of special forces troops – army and Royal Marine Commandos, the majority organised into two Special Service Brigades on the British beaches, and Rangers on the US beaches. These specialists were given a variety of tasks on D-Day. They included clearing seafront villages and towns of the enemy, linking the beachheads creating a single continuous lodgement, and, in the case of the British 1st Special Service Brigade, seeking a rapid junction with the British 6th Airborne Division in order to support their flank defence beyond the River Orne. Meanwhile, the US 2nd Ranger Battalion was ordered to capture the German cliff-top battery at Pointe du Hoc. Yet the problem still remained of how to get these men inland without suffering unacceptable casualties on the beach. It was an issue that attracted even more concern following the decision on 1st May 1944 that, due to Rommel’s sowing of extensive beach defences in the first half of 1944, the landing would have to be made in daylight and at low tide so that beach obstacles would be visible. Allied troops would now have a greater distance to cover from landing craft to seafront and without the cloak of darkness! Luckily, the solution was already well in hand. It lay in the development of a number of specialised armoured vehicles, specifically designed to take on the beach obstacles and seafront defences. The unorthodox nature of the military requirement was echoed by the appointment of the British Major-General Percy Hobart, an idiosyncratic thinker and early tank enthusiast, to take charge of the design, development and tactical doctrine of these vehicles. They quickly became known as “Hobart’s funnies” and included:

Whilst the Americans did utilise the DD tanks, ”Hobart’s funnies” were primarily to be used on the British and Canadian beaches where they would be formed into armoured assault teams under the auspices of 79th Armoured Division. American commanders felt that this specialist armour would have a more limited impact in the early stages of the landings and, instead, put their faith in the expertise of their infantry combat engineers and Sherman tanks fitted with bulldozer blades to deal with the beach obstacles. |